library(zoo)

library(lubridate)

library(parallel)

source("common/functions.r",chdir=TRUE)23 Test Backtesting

Statistical validation of risk models requires moving beyond simple violation counting to formal hypothesis testing. Having generated backtesting data in Chapter 22, we now implement the statistical framework to determine whether our VaR and ES models perform adequately.

This chapter addresses the statistical testing of backtesting results as described in Chapter 7 of Financial Risk Forecasting. We implement VaR coverage testing to examine whether violations occur at the expected frequency, and VaR independence testing to determine whether violations are randomly distributed over time. The chapter also discusses ES backtesting challenges and limitations, along with statistical comparison across different risk modelling approaches.

Building on the backtesting data from Chapter 22, we implement the Christoffersen (1998) testing framework for VaR validation and discuss the Acerbi-Székely (2014) approach for ES evaluation.

23.1 Data and libraries

23.2 Backtest Data

We load the backtesting results generated in Chapter 22 using the LoadBacktestData() function from functions.r. This data contains VaR and ES forecasts from all four methods (HS, EWMA, GARCH, and t-GARCH) alongside actual returns and dates.

# Load backtest data using the centralized function

result = LoadBacktestData()

backtest = result$backtest

par = result$par

cat("Loaded", nrow(backtest), "trading days of backtest data\n")Loaded 6938 trading days of backtest datacat("Period:", as.character(min(backtest$date)), "to", as.character(max(backtest$date)), "\n")Period: 19971128 to 20250630 The par object contains the backtesting parameters including the confidence level and window sizes used in the forecasting process.

23.3 Reusable Analysis Functions

To support consistent analysis and visualization throughout the chapter, we create several reusable functions. This approach eliminates code duplication and ensures consistent formatting across different time periods and data subsets.

23.3.1 VaR vs Returns Plotting Function

First, create a flexible plotting function for visualizing VaR forecasts against actual returns:

plot_var_vs_returns = function(data) {

main_title = paste0("S&P 500 Returns vs VaR Forecasts")

plot(data$date.t, data$y * par$value, type='l',

main=main_title,

xlab="Date", ylab="P&L ($)",

col="black", lwd=1)

lines(data$date.t, -data$VaR.HS, col="red", lwd=2)

lines(data$date.t, -data$VaR.EWMA, col="blue", lwd=2)

lines(data$date.t, -data$VaR.GARCH, col="green", lwd=2)

lines(data$date.t, -data$VaR.tGARCH, col="purple", lwd=2)

legend("bottomleft",

c("Returns", "HS VaR", "EWMA VaR", "GARCH VaR", "tGARCH VaR"),

col=c("black", "red", "blue", "green", "purple"),

lwd=c(1,2,2,2,2), cex=0.8,bty='n',ncol=3)

abline(h=0, col="gray", lty=2)

w=seq(ymd(19900101),ymd(20301231),by="year")

axis(1,at=w,label=FALSE,pch=-0.3)

}23.3.2 Violation Plotting Function

Next, create a function for plotting violation patterns over time:

plot_violations = function(data, violations_matrix) {

colors = c("red", "blue", "green", "purple")

methods = c("HS", "EWMA", "GARCH", "tGARCH")

plot(data$date.t,violations_matrix[,1] ,

type='p', pch=20, col=colors[1], main="VaR Violations",

xlab="Date", ylab="", ylim=c(0.5, 4.5), yaxt="n")

for (i in 2:4) {

points(data$date.t,violations_matrix[,i]*i,

pch=20, col=colors[i])

}

axis(2, at=1:4, labels=methods, las=1)

w=seq(ymd(19900101),ymd(20301231),by="year")

axis(1,at=w,label=FALSE,pch=-0.3)

}23.3.3 Violation Analysis Function

Finally, create a function for calculating violation statistics and generating summary tables:

# Define VaR methods globally for use throughout the chapter

VaR_methods = c("VaR.HS", "VaR.EWMA", "VaR.GARCH", "VaR.tGARCH")

# Create reusable violation analysis function

create_violation_analysis = function(data, par, data_name = "Dataset") {

# Create violations matrix

PL = data$y * par$value

Violations = matrix(0, nrow=nrow(data), ncol=length(VaR_methods))

colnames(Violations) = VaR_methods

# Create binary violation indicators (1 = violation, 0 = no violation)

for(i in 1:length(VaR_methods)){

VaR_values = data[,VaR_methods[i]]

Violations[,i] = ifelse(PL < -VaR_values, 1, 0)

}

# Calculate violation statistics and create summary table

violation_counts = colSums(Violations)

violation_rates = violation_counts / nrow(Violations)

expected_violations = par$p * nrow(data)

expected_rate = par$p

# Consolidated violation summary

violation_summary = data.frame(

Method = gsub("VaR\\.", "", VaR_methods),

Violations = violation_counts,

Rate_Percent = round(violation_rates * 100, 2),

Expected_Count = round(expected_violations, 1),

Expected_Rate = round(expected_rate * 100, 1),

Difference = violation_counts - expected_violations,

Performance = ifelse(abs(violation_rates - expected_rate) < 0.01, "Good",

ifelse(violation_rates < expected_rate, "Conservative", "Liberal"))

)

cat(data_name, "Violation Analysis:\n")

print(violation_summary)

# Identify best performing method

best_method = which.min(abs(violation_rates - expected_rate))

cat("\nClosest to expected rate:", violation_summary$Method[best_method], "\n")

# Return results for further analysis

return(list(

violations = Violations,

summary = violation_summary,

rates = violation_rates,

counts = violation_counts

))

}23.4 Initial data exploration

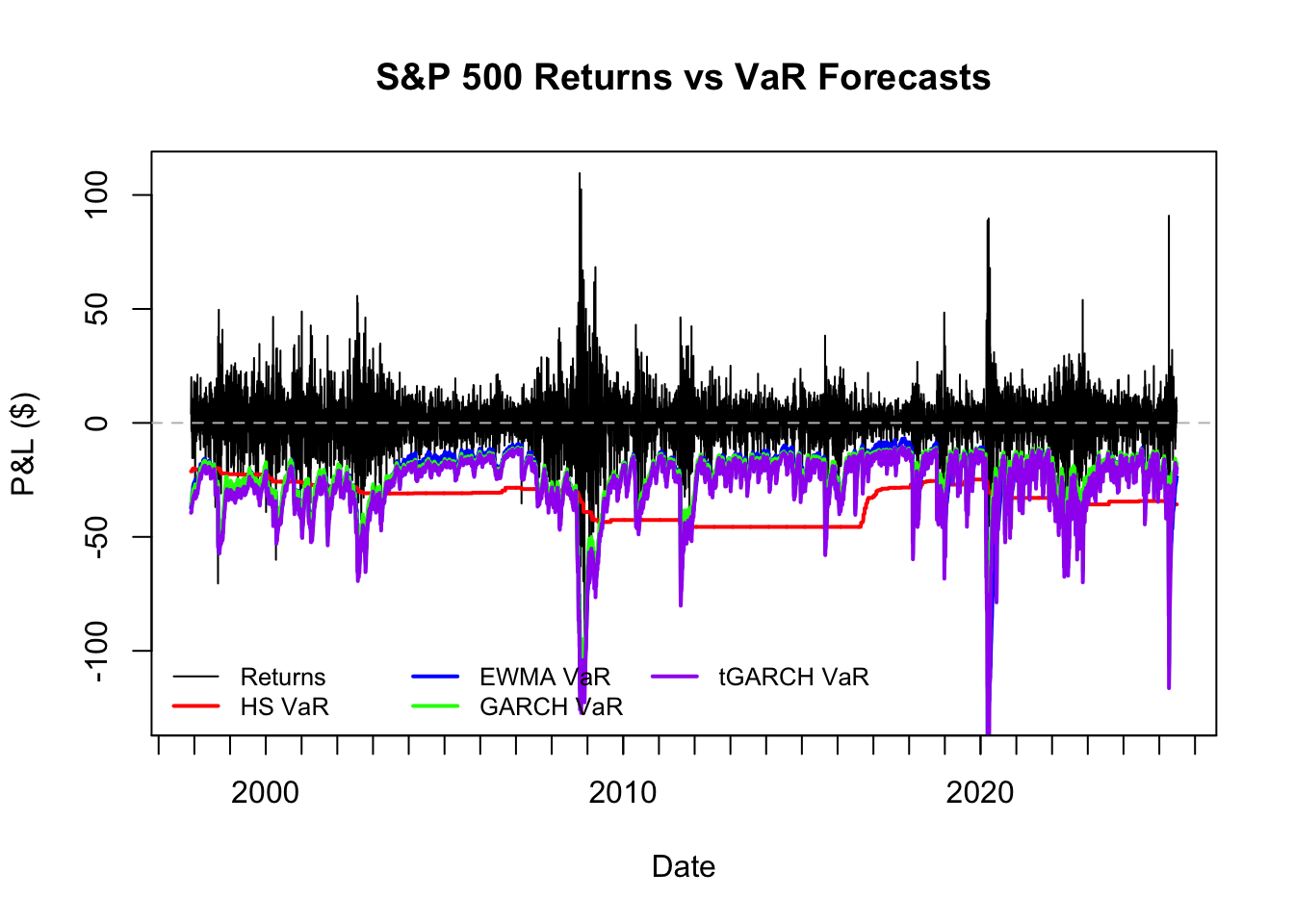

The backtest data frame contains VaR and ES forecasts for all methods, along with actual returns and dates. We can visualise the forecasts against actual returns to see how well our models capture market risk.

plot_var_vs_returns(backtest)

# Summary of the loaded data

cat("Backtest period:", as.character(min(backtest$date)), "to", as.character(max(backtest$date)), "\n")Backtest period: 19971128 to 20250630 cat("Number of trading days:", nrow(backtest), "\n")Number of trading days: 6938 cat("Estimation window size:", par$WE, "days\n")Estimation window size: 2000 dayscat("Testing window size:", par$WT, "days\n")Testing window size: 6938 dayscat("VaR confidence level:", (1-par$p)*100, "%\n")VaR confidence level: 99 %23.5 Violations

A violation occurs when the actual loss exceeds the VaR forecast. For a well-calibrated VaR model, violations should occur at the expected frequency — a 1% VaR model should be exceeded roughly 1% of the time.

We create violations by comparing actual losses to VaR forecasts and convert them to binary indicators for systematic analysis.

# Use function to create violation analysis for full dataset

violation_results = create_violation_analysis(backtest, par, "Overall")Overall Violation Analysis:

Method Violations Rate_Percent Expected_Count Expected_Rate

VaR.HS HS 107 1.54 69.4 1

VaR.EWMA EWMA 151 2.18 69.4 1

VaR.GARCH GARCH 136 1.96 69.4 1

VaR.tGARCH tGARCH 87 1.25 69.4 1

Difference Performance

VaR.HS 37.62 Good

VaR.EWMA 81.62 Liberal

VaR.GARCH 66.62 Good

VaR.tGARCH 17.62 Good

Closest to expected rate: tGARCH # Extract results for use in other sections

Violations = violation_results$violations

violation_summary = violation_results$summary

violation_rates = violation_results$rates

violation_counts = violation_results$counts23.6 Violation patterns over time

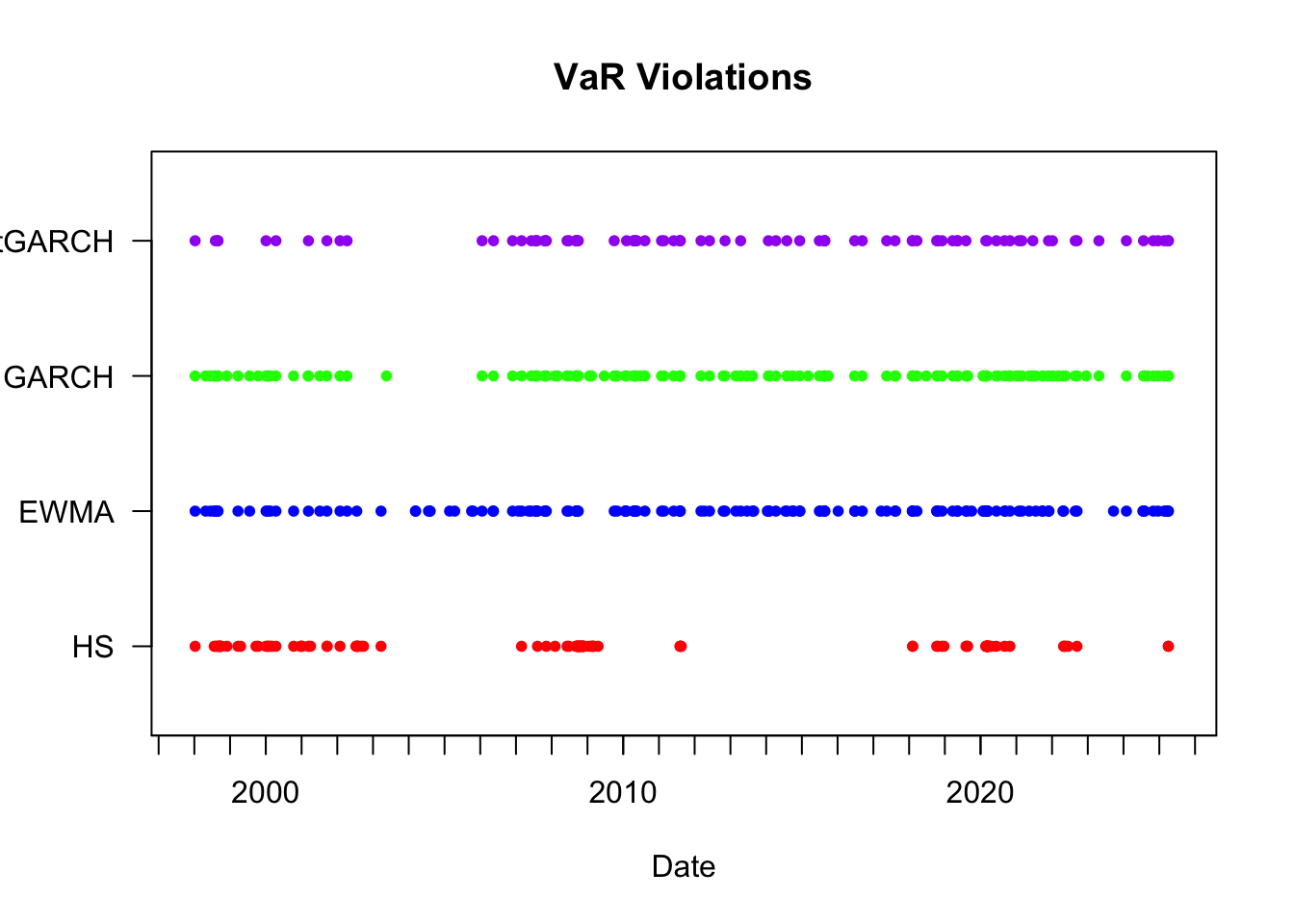

The temporal distribution of violations reveals important information about model performance during different market conditions. Well-calibrated models should show violations distributed randomly over time, while clustering indicates the model fails to adapt quickly to changing volatility.

# Use function to create violation plot

plot_violations(backtest, Violations)

The plot reveals significant clustering during stress periods, particularly during the COVID-19 market disruption in early 2020. This clustering suggests that all methods struggle to adapt quickly enough to rapidly changing market conditions, with violations occurring in concentrated bursts rather than randomly. Such patterns violate the independence assumption required for well-functioning VaR models and motivate the formal independence testing discussed below.

23.7 Statistical Analysis of VaR

The violation analysis reveals that HS performs closest to the expected 1% rate (1.5%), while EWMA, GARCH and tGARCH all show elevated violation rates around 1.3-2.2%. However, we cannot conclude from violation counts alone whether these differences represent genuine model failures or acceptable random variation.

To make definitive judgements about model adequacy, we need formal hypothesis testing. A model showing 2.2% violations instead of 1% might still be acceptable if this difference falls within normal sampling variation. Conversely, even small deviations might be statistically significant with sufficient data.

We implement the testing framework developed by Christoffersen (1998). This framework tests two fundamental properties that well-functioning VaR models must satisfy.

23.7.1 Coverage Test

The Bernoulli coverage test examines whether the violation rate is statistically different from the expected rate. Under the null hypothesis, violations should occur at the expected frequency (1% for our models).

# Bernoulli coverage test (from Financial Risk Forecasting book)

bern_test = function(p, v) {

lv = length(v)

sv = sum(v)

al = log(p) * sv + log(1-p) * (lv-sv)

bl = log(sv/lv) * sv + log(1-sv/lv) * (lv-sv)

return(-2 * (al-bl))

}Bernoulli Coverage Test Results:

H0: Violation rate equals expected rate (1%)

# Apply coverage test to all methods

m = c("HS", "EWMA", "GARCH", "tGARCH")

coverage_results = data.frame(

Method = m,

Test_Statistic = numeric(4),

P_Value = numeric(4),

Result = character(4),

stringsAsFactors = FALSE

)

for(i in 1:4) {

test_stat = bern_test(par$p, Violations[,i])

p_value = 1 - pchisq(test_stat, df = 1)

coverage_results$Test_Statistic[i] = round(test_stat, 3)

coverage_results$P_Value[i] = round(p_value, 4)

coverage_results$Result[i] = ifelse(p_value < 0.05, "REJECT", "PASS")

cat(sprintf("%-8s: Test statistic = %.3f, p-value = %.4f (%s)\n",

m[i], test_stat, p_value,

ifelse(p_value < 0.05, "REJECT H0", "PASS")))

}HS : Test statistic = 17.678, p-value = 0.0000 (REJECT H0)

EWMA : Test statistic = 72.593, p-value = 0.0000 (REJECT H0)

GARCH : Test statistic = 50.480, p-value = 0.0000 (REJECT H0)

tGARCH : Test statistic = 4.183, p-value = 0.0408 (REJECT H0)print(coverage_results) Method Test_Statistic P_Value Result

1 HS 17.678 0.0000 REJECT

2 EWMA 72.593 0.0000 REJECT

3 GARCH 50.480 0.0000 REJECT

4 tGARCH 4.183 0.0408 REJECT23.7.2 Independence Test

The independence test examines whether violations are randomly distributed over time or exhibit clustering patterns. If violations tend to cluster, this suggests the VaR model fails to adapt quickly to changing market conditions.

A properly functioning VaR model should produce violations that appear random — like a coin flip with probability 0.01. When violations cluster together, it indicates the model reacts too slowly to volatility changes or allows repeated surprises during stress periods.

We model violations as a first-order Markov chain where today’s violation probability depends only on yesterday’s outcome. Under the null hypothesis of independence, the probability of a violation today should be the same regardless of whether there was a violation yesterday.

The test examines four transition states: - \(\eta_{00}\): No violation yesterday, no violation today - \(\eta_{01}\): No violation yesterday, violation today - \(\eta_{10}\): Violation yesterday, no violation today - \(\eta_{11}\): Violation yesterday, violation today

# Independence test function (from Financial Risk Forecasting book)

ind_test = function(V){

J = matrix(ncol=4, nrow=length(V))

for (i in 2:length(V)){

J[i,1] = V[i-1]==0 & V[i]==0

J[i,2] = V[i-1]==0 & V[i]==1

J[i,3] = V[i-1]==1 & V[i]==0

J[i,4] = V[i-1]==1 & V[i]==1

}

V_00 = sum(J[,1], na.rm=TRUE)

V_01 = sum(J[,2], na.rm=TRUE)

V_10 = sum(J[,3], na.rm=TRUE)

V_11 = sum(J[,4], na.rm=TRUE)

p_00 = V_00/(V_00+V_01)

p_01 = V_01/(V_00+V_01)

p_10 = V_10/(V_10+V_11)

p_11 = V_11/(V_10+V_11)

hat_p = (V_01+V_11)/(V_00+V_01+V_10+V_11)

al = log(1-hat_p)*(V_00+V_10) + log(hat_p)*(V_01+V_11)

bl = log(p_00)*V_00 + log(p_01)*V_01 + log(p_10)*V_10 + log(p_11)*V_11

return(-2*(al-bl))

}Independence Test Results:

H0: Violations are independent over time

# Apply independence test to all methods

independence_results = data.frame(

Method = m,

Test_Statistic = numeric(4),

P_Value = numeric(4),

Result = character(4),

stringsAsFactors = FALSE

)

for(i in 1:4) {

test_stat = ind_test(Violations[,i])

p_value = 1 - pchisq(test_stat, df = 1)

independence_results$Test_Statistic[i] = round(test_stat, 3)

independence_results$P_Value[i] = round(p_value, 4)

independence_results$Result[i] = ifelse(p_value < 0.05, "REJECT", "PASS")

cat(sprintf("%-8s: Test statistic = %.3f, p-value = %.4f (%s)\n",

m[i], test_stat, p_value,

ifelse(p_value < 0.05, "REJECT H0", "PASS")))

}HS : Test statistic = 13.343, p-value = 0.0003 (REJECT H0)

EWMA : Test statistic = 9.453, p-value = 0.0021 (REJECT H0)

GARCH : Test statistic = 1.703, p-value = 0.1919 (PASS)

tGARCH : Test statistic = 4.776, p-value = 0.0289 (REJECT H0)print(independence_results) Method Test_Statistic P_Value Result

1 HS 13.343 0.0003 REJECT

2 EWMA 9.453 0.0021 REJECT

3 GARCH 1.703 0.1919 PASS

4 tGARCH 4.776 0.0289 REJECTThe independence test results confirm the clustering patterns observed in the violation plots. Methods that fail this test show systematic dependencies in violation timing, indicating inadequate adaptation to changing market volatility. This temporal clustering violates a fundamental assumption of well-functioning VaR models and suggests these methods react too slowly to evolving market conditions.

23.8 ES Backtesting

ES, also known as Conditional Value-at-Risk, measures the average loss in the worst cases beyond the VaR threshold:

\[\text{ES}_\alpha = -\mathbb{E}[r_t \mid r_t < -\text{VaR}_\alpha]\]

Unlike VaR, ES cannot be backtested using simple violation counting because:

- ES is not defined by a single threshold breach but depends on the full shape of the loss tail

- ES is not elicitable on its own (no simple scoring function exists)

- ES is sensitive to rare, extreme losses that occur infrequently

- Traditional frequency-based backtesting (counting violations) does not apply

However, Fissler and Ziegel (2016) showed that VaR and ES are jointly elicitable, meaning we can create consistent scoring functions that evaluate both measures together, enabling meaningful backtesting.

23.8.1 The Acerbi-Székely (2019) Approach

ES can be back‑tested with the minimally biased statistic proposed by Acerbi and Székely (2019)1. The statistic

\[Z_{\mathrm{ES},t}=\text{ES}_t - \text{VaR}_t - \frac{1}{\rho}\min\bigl(0,\,y_t + \text{VaR}_t\bigr)\]

where:

- \(\text{ES}_t\) = ES forecast for day \(t\) (predicted expected shortfall)

- \(\text{VaR}_t\) = VaR forecast for day \(t\) (predicted value-at-risk threshold)

- \(y_t\) = realised return for day \(t\) (actual portfolio return, negative for losses)

- \(\rho\) = confidence level (e.g., 0.025 for 97.5% confidence)

- \(\min(0, y_t + \text{VaR}_t)\) = captures only cases where actual loss exceeds VaR threshold

The formula provides unbiased estimates when the ES model is correctly specified up to a small prudential bias that vanishes when the accompanying VaR forecast is exact. The bias disadvantages the modeller and hence provides a conservative assessment.

23.8.1.1 Implementation

# Minimally biased ES backtest

Z_ES = function(ES_t, VaR_t, y_t, p = 0.025) {

ES_t - VaR_t - (1 / p) * pmin(0, y_t + VaR_t)

}

# Example implementation for first method

method_name = gsub("VaR\\.", "", VaR_methods[1])

var_forecasts = backtest[,paste0("VaR.", method_name)]

es_forecasts = backtest[,paste0("ES.", method_name)]

PL = backtest$y * par$value

# Identify violation days

violations = PL < -var_forecasts

violation_days = which(violations)

if (length(violation_days) > 0) {

# Compute statistic on violation days

Z_values = Z_ES(es_forecasts[violation_days],

var_forecasts[violation_days],

backtest$y[violation_days])

t_test = t.test(Z_values, mu = 0)

print(paste("Method:", method_name))

print(paste("T-statistic:", round(t_test$statistic, 3)))

print(paste("P-value:", round(t_test$p.value, 4)))

}[1] "Method: HS"

[1] "T-statistic: 28.096"

[1] "P-value: 0"23.8.1.2 Interpretation

- Negative t values show ES underestimation

- Positive values point to overestimation

- Small magnitudes imply consistency

A relative variant divides \(Z_{\mathrm{ES},t}\) by \(\text{ES}_t\) and provides a scale-free factor useful for multipliers. This relative measure is particularly valuable for regulatory capital calculations where proportional adjustments to ES estimates are required.

Acerbi, C. and Székely, B. (2019). The minimally biased backtest for ES. Risk, September 2019, 76-81.↩︎